By Katie Kish, Stephen Quilley and Jason Hawreliak

This article describes a Metcalf-funded research project investigating Maker culture as the basis for a relocalized, community-based green economy. (Green Prosperity and the (Re)Maker Society: Integrating the low growth economy with community self-development, artisanal skills and enhanced cultural participation (Metcalf Foundation, $38,000) – Stephen Quilley (PI), Jason Hawreliak (Post-doc Researcher), Katie Kish (Graduate Research Assistant), Marcel O’Gorman (Co-App.), Rob Gorbet (Co-App).) The project is part of a joint research programme of the Waterloo Institute for Social Innovation and Resilience (WISIR – http://sig.uwaterloo.ca/about-the-waterloo-institute-for-social-innovation-and-resilience-wisir) and the Alternatives to Conventional Growth stream of the Waterloo Institute for Complexity and Innovation (WICI http://wici.ca/): ‘Navigating the Anthropocene: Towards an Alternative Modernity for an Era of Limits’. Further details are available at www.remakersociety.com

This Metcalf Foundation-funded pilot study concerns possible alternatives to the consumer society. Focusing on the emerging Maker culture, we are interested in (i) the extent to which open source technology is transforming the possibility for local, low energy, small-scale production and maintenance of high tech goods that have hitherto been the preserve of large scale, global industry and (ii) whether participation in Maker culture has the potential to become an effective driver of cultural-psychological and behavioural change with regard to consumerism. By putting on, and funding, a series of Maker workshops, the initial phase of research has involved establishing on-going relationship with the vibrant local maker community, and gathering preliminary data about the motivation of participants and the impact of the experience.

While limits to growth (Meadows et al. 1972) quelled confidence in progressivism of post-World War II putting patterns of development through industrial society into question, the idea of limits has had little traction on policy or politics. This is primarily because both development in the Global South and the social compact underpinning stable liberal politics in the North, both depend upon economic growth. At the same time, the trajectory of technological innovation remains intimately entwined with the high and excessive product cycling associated with consumer society. Although there is a compelling theoretical rationale for low/no growth economics (Victor 2008; Jackson 2009), this vision has not been demonstrated ‘on the ground’. The putative green economy has achieved little traction and it has been difficult to envisage it emerging organically at the level of local communities and bioregions.

The ‘small is beautiful’ vision of local, artisanal, green production for need has been a recurring feature of Romantic counterculture for two centuries. But for most of this time, community production seemed incompatible with innovation and progressive technology based on the application of science. Over the last decade, this situation has begun to change. A network of maker spaces, hacking clubs and online peer-to-peer (P2P) design collaborations are pointing the way to a different kind of economy: high tech but local, participatory and networked. The maker movement (Anderson 2012; Hatch 2013) has the potential to challenge the established business models and resilient, self-reinforcing systems of the growth economy.

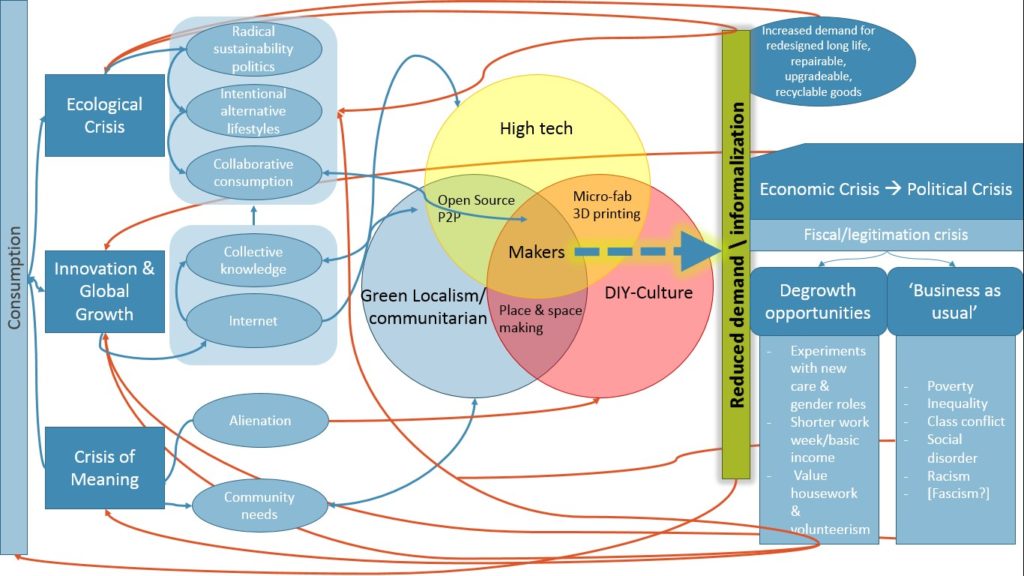

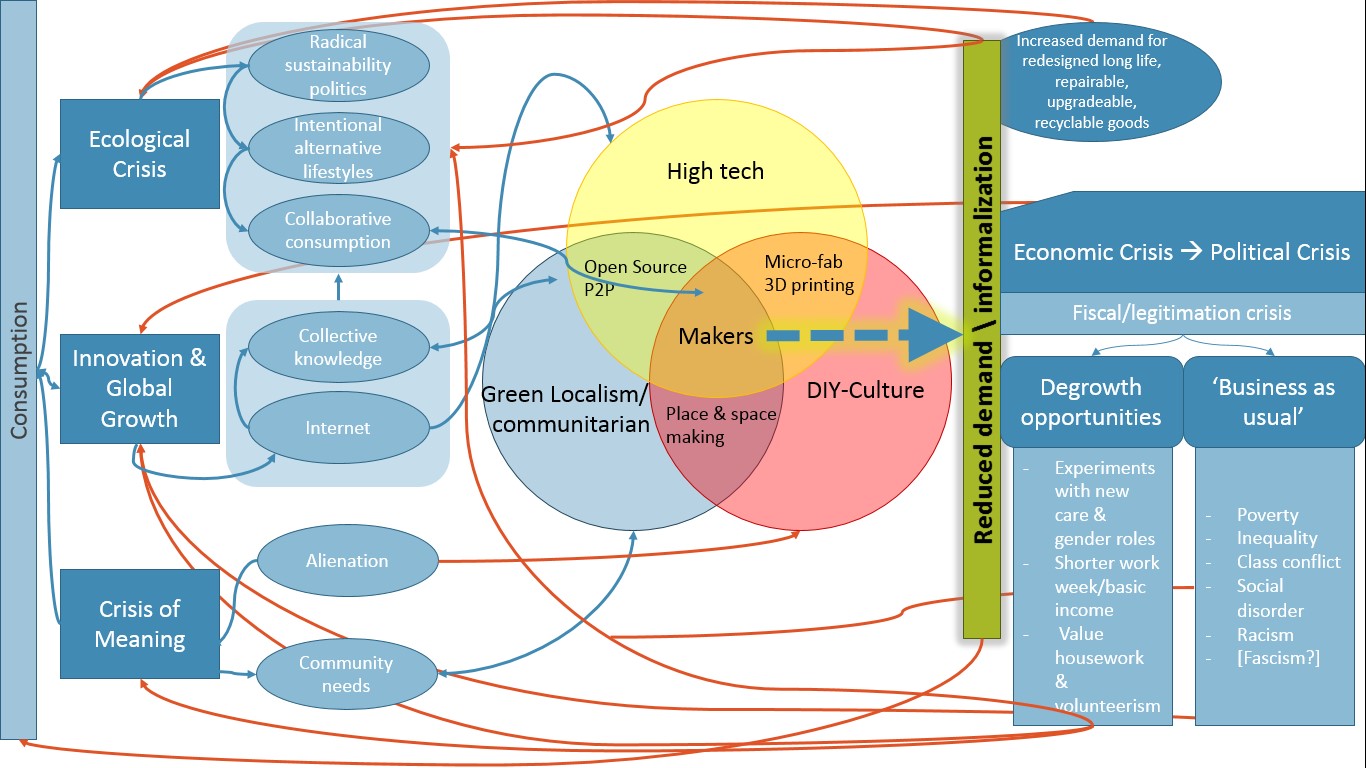

Our idea is that the habit of actually making things may challenge logic of passive consumption whilst engendering a new kind of community-based economy. In image 1, if makers are able to reduce demand and informalize the economy sufficiently – there could be large scale change. To test this idea, we are researching how the convergence of (i) new communication and organizational [open source, P2P] technologies associated with local networks and the Internet, with (ii) emerging micro fabrication technologies (e.g. 3d printing) are creating as yet untapped possibilities for small-scale, community-based economy which combines artisanal craftsmanship with both technical innovation and a much more integrated recycling, reuse and repair of material objects.

But even if new technology brings a community-based economy of participatory fabrication one step closer, it is an open question whether people really want to embrace a life of active making, remaking, repair and recycling. For this reason, the second theme of the project addresses questions of motivation and psychology. Building on pioneering work by Ernest Becker (1973), Janis Dickinson (2009) has suggested that, in an increasingly secular and rational world, consumption has become a primary source of meaning and existential security. ‘Terror management’ research has confirmed that fear of death constitutes a pervasive driver of human behaviour (Greenberg, Pyszczynski, and Solomon 1986; Arndt et al. 2004; Kasser 2003; Kasser and Sheldon 2000). In all societies a central role for culture is to sanction particular roles or activities – ‘hero/ immortality projects’, ‘symbolic selves’ – through which individuals can accrue social esteem and/or symbolic or literal immortality. Dickinson suggests that consumerism functions as a highly effective hero/immortality project. Any mass migration to a radically different worldview and associated behaviours would depend on the emergence of distinctively green ‘hero’ or ‘immortality projects.’ Our research is beginning to test the extent to which the emerging Maker culture might function as an arresting and compelling alternative hero/immortality project.

The long-term aim of this project is to test the capacity of community-based hacking spaces and Maker projects to engage ordinary people, unpick the psycho-cultural attractions of consumerism, change behaviour and transform local economies. Working closely with local Maker clubs (KWArtzLab, DIYode and the Maker Club for Kids) and collaborating with Open Source Ecology project in Missouri, we have organized a series of maker workshops:

- Power Cube Build: Collaborating with Open Source Ecology, this project involved basic metal working skills including welding, grinding and cutting metal to create a 1’x1’ four-horsepower engine. This workshop took place at DIYode in Guelph over 3 days, Ontario with 15 participants, aged 14-29.

- Gumball Machines: Collaborating with the Kitchener Maker Club for Kids, this workshop involved making a wooden gumball machine with children. This workshop took place at The Museum in Kitchener, Ontario. Two sessions ran over two days with a total of 35 children, aged 6 – 13, participating.

- Sewing and Textiles: This workshop taught the basics of sewing ending with a personally designed and created tote bag. This workshop was held at Kwartzlab in Kitchener, Ontario with a total of 15 participants over two days.

- Hacking Electronics with Arduino: This workshop was held at the Digital Media Lab in Kitchener, Ontario. There were a total of 14 participants who were taught the basics of programmable LEDs to make a custom electronic wearable.

- Short Workshop Series: University of Waterloo graduate students will run maker workshops on yurt construction, bicycle repair, soap making and recycled tire jewellery. These workshops will run as part of the Faculty of Environment Year-End Festival in March, 2015.

With these preliminary workshops we have consolidated a working relationship with the local Maker community and begun to gather data about the experience of participants and the impact of the experience. The participants were gathered through the various e-mail lists of the groups we partnered with. The primary methodologies employed were participant observation during the workshops, short likert scaling surveys following the workshops and open-ended interviews with participants. Preliminary results indicate that a) makers have a higher propensity to make/repair goods instead of consume them, b) making increases self-esteem, c) there is a very clear gender divide between various types of maker projects requiring conscious inclusion of women, d) maker spaces need reorganization to be more inclusive spaces for wider community engagement and e) primary drivers of ‘making’ are for personal interest and to opt out of the traditional economic system.

Image 1: Consumption drives the ecological crisis, has a feedback cycle with innovation and is created by a crisis of meaning. If the maker movement becomes strong enough, coupled with additional degrowth opportunities, it could combat some overarching issues.

The seemingly prosaic focus for this pilot project, maker culture in southern Ontario, may not at first sight seem revolutionary or even disruptive. But as we have tried to capture in Figure 1, maker culture could be prefigurative of a post-consumer, post-capitalist society. For the first time, new technologies of communication and production make it possible to conceive of a relatively high tech material culture being produced, maintained, and repaired in bioregional and community contexts.

Despite theoretical and early optimism in the project and future of Makers two issues emerged. First it is unclear what the small possible community is that would still be able to uphold a functioning Maker culture. Second, this first problem is particularly glaring as the smaller centres and projects still rely on ‘big box’ retailers for their projects and space furnishings. However, Makers still point the way, at least potentially, to a low overhead, low cost and highly participative mode of production that echoes horticultural and hunter-gather ways of being and making abandoned as we embraced the industrial society. Having said this, our theoretical framing of the reMaker society through the lens of complex adaptive systems, also draws attention to dynamic instabilities that would certainly be associated with the emergence of any radical political economy of peer production. Disruptive innovation and ‘creative destruction’ don’t sit easily with the benign depictions of steady state or low/no growth economics that dominate the discourse of ecological economics (Victor, 2008; Jackson 2009). However imperative from an ecological point of view, degrowth via participatory peer production would be a bumpy ride (Quilley 2012).

References

Anderson, Chris. 2012. Makers: The New Industrial Revolution. First edition. New York: Crown Business.

Arndt, Jamie, Sheldon Solomon, Tim Kasser, and Kennon M. Sheldon. 2004. “The Urge to Splurge: A Terror Management Account of Materialism and Consumer Behavior.” Journal of Consumer Psychology 14 (3): 198–212. doi:10.1207/s15327663jcp1403_2.

Becker, Ernest. 1973. The Denial of Death. New York: Free Press Paperbacks.

Dickinson, Janis. 2009. “The People Paradox: Self-Esteem Striving, Immortality Ideologies, and Human Response to Climate Change.” Ecology and Society 14 (1): 34.

Greenberg, Jeff, Tom Pyszczynski, and Sheldon Solomon. 1986. “The Causes and Consequences of a Need for Self-Esteem: A Terror Management Theory.” In Public Self and Private Self, edited by Roy F. Baumeister, 189–212. Springer Series in Social Psychology. Springer New York. http://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-4613-9564-5_10.

Hatch, Mark. 2013. The Maker Movement Manifesto: Rules for Innovation in the New World of Crafters, Hackers, and Tinkerers. 1 edition. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Jackson, Tim. 2009. Prosperity without Growth: Economics for a Finite Planet. London; New York: Earthscan.

Kasser, Tim. 2003. The High Price of Materialism. 1 edition. Cambridge, Mass.: A Bradford Book.

Kasser, Tim, and Kennon M. Sheldon. 2000. “Of Wealth and Death: Materialism, Mortality Salience, and Consumption Behavior.” Psychological Science 11 (4): 348–51. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.00269.

Meadows, Donella H, Dennis L Meadows, Jorgen Randers, and William Behrens. 1972. The Limits to Growth.

Victor, Peter A. 2008. Managing without Growth Slower by Design, Not Disaster. Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.